One question that my early test readers of The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte asked me was why Betsy wanted to live in Europe so badly. What did she have against her own country?

In our current time period, when the United States is the most powerful country in the world and U.S. culture is a dominant global force, it’s hard to realize what the country was like two hundred years ago. The difference between living in an American city and living in a European capital was like the difference we’d experience between living in small-town Wisconsin and Chicago.

Look at the two graphs below, which I created using statistics I found on the Internet.

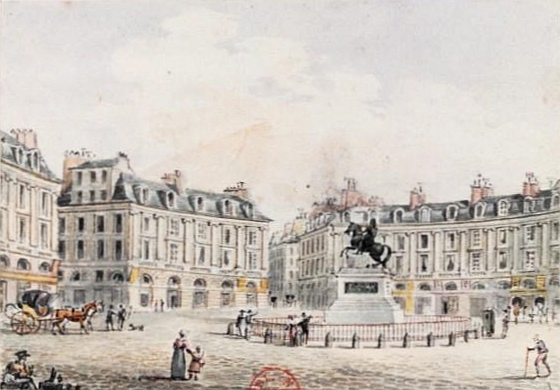

To further drive home the difference, here is an image of Paris in the early 1800s:

Place des Victoires by Victor-Jean Nicolle, via Wikimedia Commons

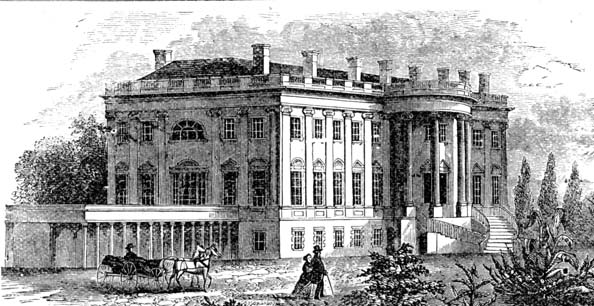

And here is the description I wrote in the novel of Washington, D.C., in 1804:

The next day, Aunt Nancy took Betsy and Jerome on a carriage tour. After Congress had decided in 1790 to build the nation’s capital in a newly created federal district, President Washington commissioned civil engineer Pierre Charles L’Enfant to devise a plan. Originally from France, L’Enfant wanted to construct a city in the European style with important buildings set far apart to allow for public gardens and plazas. At the time of Betsy and Jerome’s visit, the wide spaces between public buildings were occupied by a mix of uncleared land, small plots with cabins, and recently built houses—giving the city of Washington the disconcerting appearance of a sparsely settled wilderness with a few grandiose structures set down at random. Stories abounded of Congressmen going squirrel hunting within the city or getting mired in a swamp as they drove to their quarters at night.

Betsy was clever, ambitious, and interested in art and literature. Is it any wonder she wanted to be in Europe where the action was?