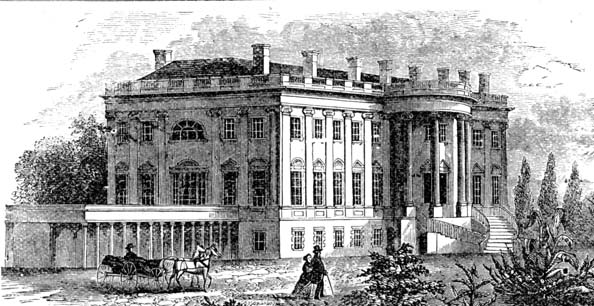

Public domain engraving, via Wikimedia Commons

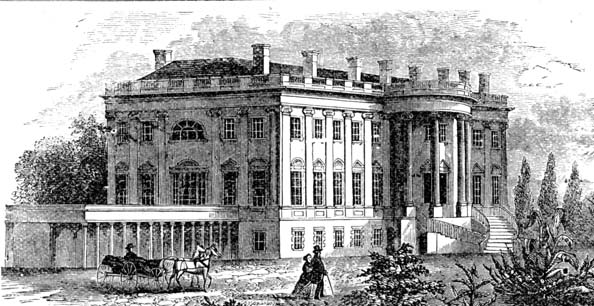

Public domain engraving, via Wikimedia Commons

A question that arises when writing historical fiction is how much description to use. One of the joys of reading historical fiction is to gain a glimpse into the past, and choosing the right descriptive details can make a distant time period come alive. However, a lot of contemporary readers are accustomed to a cleaner, more pared-down style of narrative than was typical in the past. Gone are the days when a writer can wax poetic about scenery for two pages and expect the reader to enjoy it.

I was so worried about going on too long that I actually made the mistake of using too little description in my original version of The Ambitious Madame Bonaparte. So I had to do a big revision over the summer because my editor wanted me to flesh out Betsy’s world a bit more.

Even so, I wanted to make sure that the descriptions I added carried their weight. Whenever I could, I used descriptions that added an extra layer of meaning to the novel. For example, this description not only describes the building where Betsy goes to school, it helps the reader understand the history of Baltimore and of Betsy’s teacher:

To Betsy’s delight, her father did enroll her in school. Madame Lacomb and her husband had been low-ranking nobles who had fled to Saint-Domingue during the French Revolution. Monsieur Lacomb died not long afterward, and Madame Lacomb came to Baltimore with other refugees from the slave revolt of 1793. She moved into a small, blue wooden house that was as much a survivor of a different era as she was—it had been built in the 1750s and remained standing as more imposing brick townhomes replaced the wooden houses around it.

Descriptions can also reveal a lot about your main character. People naturally relate the things they notice to their own desires and goals, as in the following scene:

Jerome and Betsy were invited to dinner at the President’s Mansion. . . . For the occasion, which would begin at 3:00 in the afternoon and last until late evening, Betsy wore a sheer gown bedecked with gold embroidery that would sparkle in the candlelight. This would be her first visit to the home of a head of state, and she wanted to demonstrate to Jerome that she knew how to dress for such occasions.

As the Smith carriage drove up to the north entrance, Betsy stared avidly at the details of the building and wondered how it compared to the palaces she would someday live in with Jerome. The President’s Mansion was an imposing light-grey stone structure, wide enough that eleven windows stretched across its upper story. The center block of the mansion was decorated with four Doric columns crowned by a triangular pediment. A small pediment also topped each window, but Betsy was surprised to see that they were not all the same. Rather, triangles alternated with rounded arches.

And sometimes, descriptions can be used to convey the humorous or unexpected:

When she and Jerome were presented to President Jefferson, Betsy was amused to see him in the characteristically plain dress he wore on republican principle: an old blue coat, dark corduroy breeches, dingy white hose, and run-down backless slippers.

Those were a few of the techniques I used to add extra layers of meaning to description.